|

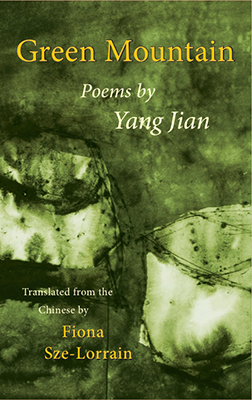

Green Mountain: Poems

by Yang Jian

Translated by Fiona Sze-Lorrain

60 Poems ~ 156 Pages (Chinese and English juxtaposed)

Price: $25.00

Format: 5 ¼” x 8 ¼” ~ Perfect Bound

Publisher: MerwinAsia

ISBN: 978-1-937385-36-1

To Order: https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/green-mountain-poems-by-yang-jian/

Reviewed by Michael Escoubas

In a moment of distinct clarity about the power and purpose of poetry, Wallace

Stevens, writing to his daughter Holly averred: “Poetry is a response to the daily

necessity of getting the world right.” That quote whisked through my mind, like

a comet in the night sky, as I worked my way through the poems in Yang Jian’s

Green Mountain.

While China’s most respected and prolific poet would no doubt disabuse the notion

that his poetry is an attempt at “getting the world right,” Yang’s work carries with it the

force of change. But ahead of change, Yang knows that history and suffering must be

engaged, treated with the deft hand of a skilled craftsman, and brought to light by a

generous sprinkling of love.

Born in 1967, Yang felt the full force of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. Green

Mountain responds to those times with clear-visioned courage. Yang never offers

platitudes, nor does he sugar-coat the truth. Therefore, readers must brace themselves

for poems that prioritize truth over beauty, reality over fantasy. It is within that thought

that we, his fortunate readers, wrap ourselves in the warmth, light, and power of Sze-

Lorrain’s compelling translation.

The collection is structured around three divisions: I. Ode to a Dead Tree; II. Mysterious

Gratitude; and III. Speak, Heart. These divisions provide anchors that readers may grasp

on the journey upward, toward the light of truth and beauty. I hasten to point out that I

greatly appreciated Christopher Merrill’s foreword and Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s illuminating

introduction both of which provided historical context.

While I feel that each poem in Part I, carries its own weight, “1967,” for me, sets a tone

not just for the poems appearing in Part I, but indeed, for the entire collection. “1967” is

fraught with images that vivify Yang’s concern for China. The poem is structured by the

repetition of “They say” in the first four stanzas. Yang then completes each stanza

with a symbol of what has been lost because of Mao’s influence on Chinese society and

culture.

The say

Snap the erhu’s cords

crush its body

We’ll no longer have its music

This two-stringed, Chinese violin is perhaps the most powerful metaphor available for

that which has been lost. Its sound, its appearance, its centuries-old history is one of three

powerful images exploited by Yang. The others: ancient trees, craftsmen such as stone-

masons and carpenters, and written history contained in manuscripts, temples, and clerics,

all come together to provide essential context for the whole volume. Yang is thus

motivated:

I’m destined not to die

but to open my mouth and speak among ruins

to open the iron door sealed by dust

Moving into Part II. Mysterious Gratitude, Yang offers the gift of hope. His Buddhist

faith lifts his heart, is the source of hope. “Mysterious Gratitude” tells the story, now

forgotten, or at least not told anymore, of well-water bestowed by a red koi. Yang is

grateful for what he has; he prays for peace, he prays for wisdom:

Here, I pray for peace: dusk to protect a farmer

who returns with his old ox

Wisdom I pray for sways like his rope

My tears will fall on this rope

by virtue of a mysterious gratitude that enfolds me in autumn

Gratitude, unbroken through generations

I live in a country that knows even well water is bestowed by heaven

Reviewer’s note: The red koi is important in this context as it stands for longevity, luck

and wealth.

The spiritual dimension in Yang’s work stands out like a searchlight shining bright in the

night. What is a culture when bereft of its stories, its legends, its impossible things? We

who live in the West, need such faith. Note this subtle image of immortality in Yang’s

short poem “Gift”:

A leaf falls without defense

Wind

Lifts it up

Without defense, it shuffles again

In its thin, dried body

love burns stronger than on a trunk

Yes, I’m immortal

a gift from these leaves

All the poems fit on single pages juxtaposed beside its Chinese original. Sze-Lorrain is at

one with Yang, sensing his love for China; she make his soul sing with passion. Her

translations are cool sips of water to be slowly savored. Keeping in mind that Yang’s life

is defined by faith and by gratitude, “Native Soil” conveys this heartfelt flavor:

When life could wither

I was just a child

In golden old maple woods

an image of me at fifteen or thirteen

Like soft river light

with a tiny beast soothing the water

and broad chimes from Sky Heart Tower

Poem after poem reveals Yang’s concern for China, his realistic sense of her pain, buffered

by hope for China’s future.

“Native Soil” segues nicely into Part III. Speak, Heart. Indeed, Yang’s heart speaks

throughout Green Mountain. However, there is a particular poignancy in poems such as

“Late Dusk”:

A horse kicks at a tree stump in the hay

Fish jump in a basket

Dogs bark in the yard

How they embrace themselves

the wellspring of sorrow

clear as the moon

running ceaseless as a river

I noted earlier that readers should be prepared for a kind of stark realism in Yang’s work.

Truth is favored over fantasy. As Sze-Lorrain notes in her introductory, most poets build

an edifice layer on layer. Yang does the opposite: he subtracts. While most people look

for and find the “good” in life, this tendency is tempered by Yang, who states in “I No

Longer Seek Outward”:

We’re wrong

to put faith in external changes

all these years

blinded by anger

Yang’s wisdom is magnified because of what he knows, because of what he and his

country have suffered. As a result, he:

No longer seeks outward

when pain contracts

I let go

moonlight blankets the mountaintop

“Speak Heart,” the section’s title poem synthesizes Yang Jian’s wide heart and his love

for China … but his heart offers a warning that should be heard by all:

Men possess so many treasures

yet without a vessel to keep them in

Return to:

|