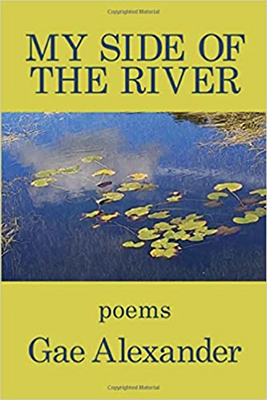

My Side of the River

by Gae Alexander

37 poems, 59 pages

Price: $14.00

ISBN: 978-1949229370

Publisher: Kelsay Books, 2019.

To order: www.kelsaybooks.com

Reviewed by Neil Leadbeater

Actress and poet Gae Alexander was born in her paternal grandparents’ home outside Roosevelt, Utah and grew up in Shelton, Washington. She studied at Brigham Young University and Kirkland College, graduating with a B.A. in literature and theatre. She is also a graduate of the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City. In addition to acting, she co-founded and served as Producing Artistic Director of American Kaleidoscope Theatre. She has taught both privately and at the Connecticut Conservatory of the Performing Arts and is a member of the Connecticut Poetry Society. ‘My Side of the River’ is her debut poetry collection.

Locality is key to several of the poems in this volume, especially those which relate to Zion National Park, Utah’s first national park, which is located in the southwestern portion of the state near Springdale. A couple of poems are set in Zion Canyon, which is 15 miles long and up to 2,640 ft deep, and forms a prominent feature of the park. The canyon walls are of a reddish and tan-coloured Navajo sandstone which has been eroded by the North Fork of the Virgin River.

In the very first poem ‘If You Will’, the imagery contained in the opening lines may well have been influenced by the experience of seeing those canyon walls in the National Park:

Take my heart. Like flint it contains

the possibility of fire. Strike it

against the coldest, hardest stone.

In ‘At the Temple of Sinawava’, a vertical walled natural amphitheatre nearly 3,000 ft deep, which is located in Zion canyon, the heart mentioned in the opening poem ‘still beats’ even though, out on a quest to absorb and wonder at the majestic awe of the canyon, Alexander has been temporarily distracted by the sudden sighting of an ambulance, paramedics and a body on a gurney:

…It’s not my day

To think of final journeys;

To consider the fatal fall

or when the heart might fail…

Canyons fill us with awe but at the same time they can make us feel small and vulnerable. That sense of awe is brought out more fully in ‘On This Splendid March Morning’ where Alexander clearly delights in her descriptions of the sheer rock walls of the canyon which are by turn ‘amber and alveolate’, ‘a honeycomb wedge’, ‘cinnamon sugar cliffs’, ‘sinuated mounds’, ‘Navajo sandstone’ and, even more poetical, ‘like huge scoops of ice-cream, / cherry-vanilla, about to melt’.

When I saw the title ‘The Turkey Tree’ I thought Alexander was referring to the Turkey oak, so-named because of its three-lobed leaves which resemble a turkey’s foot, but halfway into the poem, it transpires that the tree in the title is a cottonwood located in the Kanab Canyon where turkeys roost at night. Reading this poem, it came as a surprise to me to learn that turkeys, who spend most of their time on the ground during the day, sleep in trees at night. When I investigated this further, I discovered that, even though turkeys may use traditional roosting sites night after night, they generally use different sites and move from tree to tree, usually selecting the largest trees available and roosting as high up in them as possible. Alexander catches the drama of their arrival as they seem to come out of nowhere in great numbers to bed down for the night:

A flock of wild turkeys,

two hundred, less or more,

settle for the night in the cottonwood.

As silhouettes against the waning light,

they are perfect foliage.

Great dark leaves

on this, the perfect tree.

The nature poems are descriptive without being overdone. Experience gained in the theatre is utilised to the full in these poems which have a sense of drama about them. In ‘Wild Violets’, the principal actors are more than just plants, they are sentient beings with open, guileless faces, ‘a chorus line of hundreds’ on her April lawn. In ‘February Morning’ everything in nature, like an actor, ‘freezing on stage’ has come to a standstill. ‘Nothing moves’ and ‘Morning is stunned’ and yet, within this period of inactivity, Alexander draws our attention to last year’s hydrangeas whose desiccated blooms are described as being ‘bouffant’ as they hang on to their stems. The word stands out on account of its French extraction and its depiction of something that is round and puffy in quality.

‘In May After Rain’ utilises a well-known dramatic technique by lulling readers into a false sense of security in the first stanza only to jolt them into a painful memory in the second where ‘Grief, wholly unexpected, / squeezes your heart in its fist’.

Have you ever looked hard at an apple? Not a Granny Smith but a Braeburn – in other words, not one that is green all over but one that is flecked with a myriad shades of red? In ‘Bounty’ Alexander refers to them as ‘Gold burnished with rose / deep garnet; pink with sage-green striations; / lipstick red: and a perfect May-like green’. For Alexander, these colours are one of life’s ‘ordinary miracles’.

There is another side to this collection, a darker side, in which Alexander charts a world of unspeakable evil and cruelty. It is a cruelty that ‘carries the force of a hammer’. In ‘Memory From a Parched Place’ she describes a specific incidence of cruelty being meted out to an insect she once witnessed when living in the desert and in ‘Should I Be Blue?’ she writes about the modern phenomenon of faceless strangers hurling insults on social media. In ‘When the Least of Us’, a poem that arose out of reading an account of an horrific act of violence in the Congo, she wonders why

…it is we who get to thank God for daily bread

and the blessing of ordinary days

when the least of us His children,

they who suffer most the horrors of His world,

are surely as deserving.

Finally, in ‘Arithmetic’ – a chronological account of man’s inhumanity to man, good and evil are weighed in the balance where the scales are set in terms of plus and minus, addition and subtraction, which prompts the final line: ‘What does it all add up to?’

In the light of all that has gone before, Alexander, in ‘Self-Centred Exercise’ asks the question many poets have asked themselves: ‘Is poetry a trivial pursuit? / A mere self-centred exercise?’ To which I would reply that poetry is healing. It is a means by which we can express our deepest joys as well as our deepest fears and, by sharing them with others, we can bring a measure of healing and peace to a world so badly in need of both. |