|

Comment on this

article

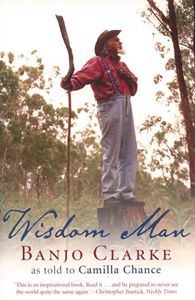

Wisdom Man: Banjo Clark

as told to Camilla Chance

285 pages $17.95

Penguin Books Australia, Ltd.

www.penguin.com.au

Reviewed By: Ed Bennett

Winston Churchill said “History is written by the victors”. In the case of the indigenous peoples of the world, history is written in blood by the point of a bayonet. This is the dark, unmentioned underside of the Age of Exploration and whether by the hand of a colonial power or of settlers looking to expand their territory, the story is similar and the outcome preordained by the overwhelming weaponry and sheer numbers of the invading forces. The stories of indigenous people, be they Aborigines, Native Americans, the Amazonian tribes or Maoris, is depressingly the same. First person accounts by surviving indigenous people frequently fall into the realm of victim literature because the vocabulary is the same: massacre, starvation, disease, forced resettlement. Even the words of the survivors are given a patina of European phraseology that loses the simplicity and openness of the original language.

Wisdom Man is the story of Banjo Clark, the late leader of the Framlingham Aboriginal Settlement in Warranambool, Australia. The story of his life and of the Australia that he experienced across nearly eight decades was recorded by Camilla Chance, his biographer and friend. Ms. Chance took care to record the story in Banjo Clark’s own words, in sentences alive with colloquialisms and an occasional grammatical faux-pas. In my opinion, this not only adds a great deal of verisimilitude to Banjo’s story; it speaks highly of the faithful rendering of this history of Banjo and his people. Ms. Chance respected her subject and trusted his words to the extent that she gave us an unchanged monologue from a man who saw both the evils and the good of 20th Century Australia.

What sets this book apart from others of this genre is the fact that the tone is conciliatory and he does express hope for relations between Whites and Aborigines. Banjo Clark does not pull punches and does describe beatings and massacres as well as the missteps taken by himself and his fellow Aborigines. There is no demand for reparations implicit in the book save for the desire to see Aboriginal lands maintained and opened to the tribes. Early in the book, Banjo brings up the use of words like “half caste” and “mixed race” and concedes that they are not used today in politically correct conversation. He uses them, nonetheless, because as he says, these were the words he heard for a long time and they are the way he perceives people. Yet also, from the outset, he explains that he doesn’t use these labels as exclusionary. Even more so, he feels that the Aboriginal understanding of the world around us is a mindset that should be universal regardless of a person’s origins.

Banjo Clark’s conciliatory tone speaks from the soul. One would expect a diatribe about how the original Australian people were displaced by Europeans but Mr. Clark opens himself to the suffering of others when trying to understand their actions toward his people. He says: “We’re not angry about it, I say. We’re just sad. I don’t blame the white men for their barbaric ways toward us. White men came to this country in chains and were treated like animals themselves – how would we expect them not to act like animals?...How can you bear grudges, how can you be angry, when it happened to indigenous people all over the world? Of course it shouldn’t have, but lots of people in authority say that it never happened. But it did….our people was put on missions and not allowed to leave, and handed out so little tucker (rations) that they was starving and dying by the hundreds of ordinary flu and measles, and things like that. Others were put on small islands away from their homelands, and died of broken hearts looking over the water at their own spiritual place.”

In those words there are some Americans who hear the echo of Wounded Knee, Sand Creek, the Trail of Tears, yet the words have a dissonance to us because no blame is placed and one almost pities the Conquistador or cavalryman who performed the work of “pacification” of the native people. Like the Native people of America, the Aborigines were branded pagans and savages. Here, in Banjo Clark’s words, is an expression of the highest principals of Christianity by a man raised to revere the spirits of the Australian bush and who practiced the Baha’i faith at the end of his life.

Camilla Chance has done an extraordinary rendering of Banjo Clark’s life. Like other Indigenous people, the Aborigines have an oral tradition. Other attempts at presenting “as told to” oral traditions almost invariably bear the literary fingerprints of the person writing it down. This is not the case with Ms. Chance. Banjo Clark’s words, his homily, if you will, had the familiar cant of my grandparents telling me about their lives so many years ago. There are no political irons in the fire in this book and the truth and faithfulness of her recording is apparent. In a world where native populations are declining we are losing the voices of the people who lived on the vast majority of the world’s surface. We find ourselves staring at ruins, the context completely lost because the people who built the structures were destroyed by progress. This is Camilla Chance’s greatest contribution: that she gave us an unadulterated book of ideas and insights from a great man among his people in his own words and from an Aboriginal viewpoint.

If you are looking for a biography of someone who led an army or who threw off the oppressors yoke, this is not your book. This is the story of someone living at the top of his potential, occasionally hurt, occasionally faltering but always living a completely honest and decent life. Camilla Chance has presented this unique life and underscored it with an honesty not often found in biography.

Many of us admire Winston Churchill for his brave resistance to the forces of totalitarianism. There are those of us, however, who remember his other saying: “The wogs start at Calais”. There are far fewer who admire Gandhi, who had no army or anything else but human dignity and morality in his arsenal. Banjo Clark, like Gandhi, was born into colonial repression and like Gandhi he faced it directly with his own wit and his own considerable personal strength. Read Churchill’s biography to learn how to be a statesman. Read this book to learn how to be a better human being.

Return to:

|