|

Our Aching Bones, Our Breaking Hearts: Poems on Aging

by Joel Savishinsky

18 Poems ~ 50 pages

Price: $14.00

Publisher: The Poetry Box

ISBN: 978-1-956285-33-8

To Order: Amazon.com

Reviewed by Michael Escoubas

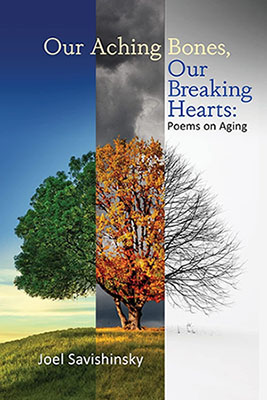

Upon receiving my review copy of poet Joel Savishinsky’s new collection, the cover caught my attention. I noticed how the image pictures the life-cycle: Spring and Summer’s lush green foliage; Autumn’s beautiful earth tones, early signs of decline; finally, Winter’s barren-ness, the foliage does not cling, cannot cling to the branch, but must yield to a design not its own.

I noticed too, the sky-tones which accompany each image: blue, then an ominous buildup of black and gray; finally winter’s bleak white. All of these enticed me to think deeply, stimulated by the cover’s symbols and images, drawn from the natural world, made real by the poem’s inside.

Joel Savishinsky, anthropologist and gerontologist is eminently qualified to opine about aging. His fifty years of research, teaching, and writing, the world over, become self-evident in the poems themselves. I sense, however, that lessons learned in the crucible of life, are the true informants of his writing.

The title: Our Aching Bones, Our Breaking Hearts provides an outline. Consisting of nine poems each, I take Our Aching Bones as emphasizing the physical side of aging; Our Breaking Hearts as featuring the emotional/psychological side. However, the author is not chained to arbitrary categories. His poems move with ease, overlapping, as the muse inspires. Don’t look for easy answers to life’s hard questions. Savishinsky will have nothing of platitudes; he goes deeper. He does so, I would add, with a compassionate heart. He lives within the oeuvre of his own writing.

The goal of this review is encouragement to all who are geriatrics in process. How do we, even as we age, live lives of freshened vigor? Joel Savishinsky’s insightful poems shed light upon our path.

The winsome “Waking Up At 77,” strikes a familiar chord with your reviewer who has just turned 76:

You’re not complaining. Just reporting.

You lie there, keeping still, and wait,

not moving. Because you know

as soon as you change position,

something will hurt, and you don’t

want to know what that something

is today. Curiosity has become

very discrete, and sleep the rarest

of pleasures. Rip Van Winkle must

have known all this. No waking.

No questions. No pain.

The day can wait.

Savishinsky’s writing style is conversational, welcoming. Metaphor is his specialty as shown in the opening stanza of “Reading In My Hospital Bed.” He hears planes “grinding / the night up into / a dark grain. …” The poem continues, developing the theme of aging in the eyes of his children, who “would now / never cease to worry / and so had made me old.” The poem expresses the hope he might be forgiven for his shortcomings and that he might forgive himself. I appreciate the marriage of both physical and emotional impacts of aging. I also see the poet’s “layering” of meaning. “Book” may indeed, be interpreted literally or as an image of the poet’s life. By extension: are we the “book” that must be read?

Moving into part 2, Our Breaking Hearts, Savishinsky calls upon the seasons to develop his thesis that all of life is worth the best that we have. “Ambush” is set in June’s virile fullness. The poet sets out on a walk. He does not intend to write a poem. But finds himself praising the world around him … “curtains of forsythia,” “scents of lilacs,” “starfish outbursts of dogwood.” His mind reaches back, “over the lawn of a small-town house where / my infant sons slept in their carriages.” This poem features an ironic ending you won’t want to miss.

“Orchard in Autumn,” like the season itself, registers a somber tone. Savishinsky’s take is one of heroic realism. (Above I noted that this poet does not offer easy answers). “Nothing seems to be what it is. / The carrots are like cardboard. / Tomatoes: tasteless. Too many / mealy melons …” As the poem continues, the poet finds reasons to praise these natural life-processes. There is even a creation reference to the Tree of Good and Evil and how “autumn fruit embodies the Fall itself.”

These days a lot of people are writing poems about aging. However, I’ve yet to find a more compelling poem than Joel Savishinky’s “How to Make Love to the Dead.” The poem calls upon the “imagination’s fingers” to know and see the faces of those we once knew and loved and who knew and loved us. Its closing stanza, for this reviewer, says it all:

You make love to and with them when

re-making this world a little more like

the one they wanted, by tasting the warmth

of their smile at your saddest moments, and

discovering that the broken skin from each

of those mutilated memories is finally beginning

to knit into a complete, forgiving embrace.

|